|

| Stran-Steel Advertisement, 1944 Source: Vanderbilt, 67 |

|

| Stran-Steel Advertisement, 1943 Source: Vanderbilt 67 |

As early as 1943, the Stran-Steel Company began positing

potential roles of Quonset Hut after the war. Advertisements during the

wartime portrayed a post war society of modern, and Quonset-like, architecture[1].

|

| Aerial perspective drawing of Camp Parks Chapel and Library, Dublin, CA (1945) Source: Carter 55 |

|

| Camp Parks Chapel and Library, Dublin, CA (1945) Source: Carter 55 |

|

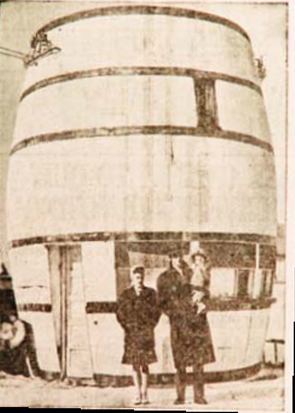

| Ardell Hagen bought a gigantic barrel that housed a hamburger stand and converted it into a two-story home for his family, 1946 Source: Vanderbilt 70 |

When the war ended, it brought about a housing shortage in the US, as 12 million men turned from the battlefield towards private

life. In addition, wartime marriage, rural to urban migrations, and a population

boom of 8 million people in 5 years also contributed to the problem[3].

Even if 1.2 million permanent homes were to be built every year in the U.S, it

would still be 10 years before everyone was housed[4]. Housing was so scarce that veterans and their family were forced into unconventional homes, such as a renovated barrel-shpaed burger stand, a beer-van-turned-apartment, and even a renovated mortuary[6].

| ||

| Display model of a Quonset house erected by the Great Lakes Steel Corporation in Mansfiled, OH (1946) Source: Vanderbilt 87 |

|

| Spread from "A Home from a Quonset Hut," House Beautiful (Sept 1945) Source: Vanderbilt 78-79 |

Quonset Huts were sold by the Stran-Steel company for $873.

The buyer would receive the kit and framing of a 20’ x 40’ hut that would

provide shelter for 30 barracks during the war, but was converted into three apartments; 2

bedrooms, a kitchen, a living room, and a bath. However, the buyer had to erect and insulate the hut himself[5].

| |||

| Row of Quonset homes at Rodger Young Village, (1945) Source: Vanderbilt 72 |

|

| Directions to Rodger Young Village |

In April 1946, construction began for the first and largest

temporary veterans’ housing project, the Rodger Young Village. On 112 acres of

former National Guard Airstrip land in Griffith Park, 750 Quonset Huts were erected.

|

| Student housing at Yale University, New Haven, CT (1945) Source: Vanderbilt 87 |

|

| Veterans Village on the CSU Campus (1953) Source: Soldiers of the Ploughshare |

A shortage of student housing was also a problem on college

campuses across the United States. Quonset Huts were used as

temporary classrooms and student housing, to help house the dramatic increase in veteran enrolment after the G.I. Bill was introduced [7].

At the Colorado State University (CSU), half and

full Quonset Huts were erected at the Veterans Village on campus to accommodate

the increasing number of veteran students.

[1] Brian Carter,

War, designs and Weapons of Mass Construction (NY, Princeton Architecture Press, 2005) 51

[2] Carter 57

[3] Tom Vanderbilt, After the War: Quonset huts and their integration into Daily American Life (NY, Princeton Architecture Press, 2005) 68

[4] Hartley E. Howe, Stop Gap Housing (New York, Popular Science Publishing, March 1946) 67

[5] Howe 68

[6] Vanderbilt 67

,_27_August_2008.jpg)

.jpg)